Behind Narnia

Several years ago, my local library service ran a series of “Readers’ Days”. One of the highlights was always a panel interview with authors. And one of the questions always asked was, “What was your favorite book as a child?” Unsurprisingly, many of them mentioned The Chronicles of Narnia. But what always surprised me was that several of them then went on to say that they felt shocked (even betrayed) as adults when they suddenly realized the amount of Christian imagery CS Lewis put into the series.

The reason this baffled me was that, as a child, I was always fully aware of that imagery. Maybe that’s because I am a Christian and grew up in church circles, or because the friend who first introduced me to the series was the son of a Baptist minister. In fact, when I was about 11 or 12, I used Narnia as a handbook for life – Bible in one hand and Narnia in the other! What shocked me as an adult was when I got to university and suddenly realized what other influences CS Lewis had drawn on, some of them coming from the pagan and Muslim worlds. “I thought these were Christian books!” was my response. Now I am older, I realize of course that CS Lewis was a well-read scholar, who drew on all sorts of influences to create his beloved fantasy world. So I’d like to take a look at some of those “other influences” and where we can spot hints of Narnia within them.

Traditional Tales

Classical Mythology and Ovid’s Metamorphoses

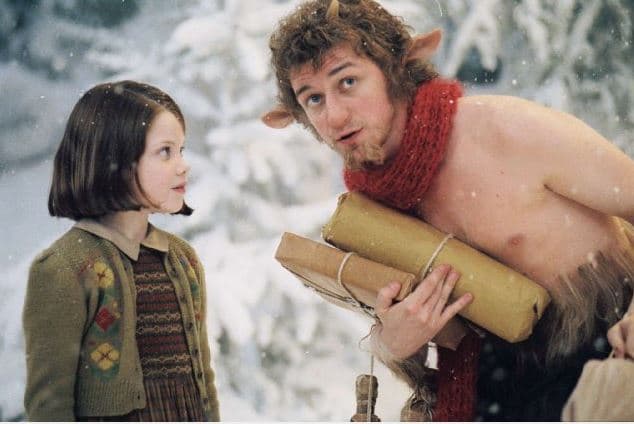

C.S. Lewis drew on classical (Greek and Roman) mythology in order to populate Narnia with dryads, fauns, centaurs and giants. Think of Bacchus and his wild girls in Prince Caspian, accompanied by old Silenus on his donkey. That’s straight out of classical mythology. I suspect Ovid’s Metamorphoses was a major source for Narnia. It’s full of stories about dryads, centaurs and the like.

There is even a Pan-like god called Vertumnus. (Mr Tumnus! Although he isn’t as nice as Lucy’s friend; let’s not go there!) Not only that, but the description in Metamorphoses of animals being born spontaneously out of the mud resembles the creation of animals by Aslan in The Magician’s Nephew, when Diggory and Polly see the ground bubble and swell, and various animals burst out of it.

Medieval Romance

Medieval Romance

The human element of Narnia draws on the tradition of medieval romance, with its knights and ladies, its quests and castles. The Hunting of the White Stag comes from this tradition, as does Queen Susan’s magic horn. The most medieval of the Narnia books is probably The Silver Chair, which follows a quest narrative (the quest to get Prince Rillian back). The account of the death of Rillian’s mother and his own disappearance is similar to the poem Sir Orfeo (a medieval version of the Orpheus legend). Sir Orfeo’s wife goes to sleep under an “ympe-tre” at midday in the month of May, becomes pale and death-like, and won’t rest until she goes back to the tree, from where she is taken away by the King of Fairies to Otherworld (from where Sir Orfeo must win her back). The fact that Eustace, Jill and Puddleglum must go to the Underworld to fetch back Prince Rillian mirrors both the classical and medieval versions of this story.

The Thousand and One Nights

The most obvious influence on Narnia of The Thousand and One Nights is the land of Calormen and The Horse and His Boy. The formal speech of the Calormenes: “Oh my father and oh the delight of my eyes”(1) mirrors the way people talk in Richard Burton’s 19th-century translation (probably the one that C.S. Lewis grew up with). “O my beloved, O light of my eyes,” says the wife of the Ensorceled Prince to her lover (2). The Calormene culture is much influenced by the exotic ideal of Arabia which many Europeans saw in The Thousand and One Nights.

But there are hints of The Thousand and One Nights even earlier in the series. For example, we are told that the White Witch is descended from Adam’s first wife Lilith, who was one of the Jinn. (Is this why she tempts Edmund with Turkish Delight??) And even Aslan’s own name is Turkish for “lion.”

Victorian and Edwardian Fantasy

As well as these much older sources, it is possible to see the influence of Victorian and Edwardian fantasy writers on the Narnia books. These writers were pioneers of the fantasy genre, and have been an inspiration to many.

George MacDonald

George MacDonald

We know that George MacDonald – author of The Princess and the Goblin, At the Back of the North Wind, Phantastes and Lilith – influenced C.S. Lewis, because he writes about his experience of reading Phantastes for the first time: “…it was as if I were carried sleeping across the frontier, or as if I had died in the old country and could never remember how I came alive in the new…” (3). I mentioned Phantastes in my post on Magic Mirrors, saying it has much in common with its contemporary, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

RELATED Top Ten Magic Mirrors

In it, we have a hero who arrives in the fairy world via a piece of furniture (in this case, his father’s writing desk), and by water flooding into his room, as happens in Voyage of the Dawn Treader. It also has talking trees, knights, living statues and the sort of kindly message of encouragement we later find in Narnia. Lilith is a later work and contemporary with Dracula. It is darker than Phantastes, with Adam, Eve and the dangerous Lilith as characters encountered by the hero. Here is another reason why the character of Lilith may have been on C.S .Lewis’ mind when he thought of Jadis, the White Witch.

William Morris

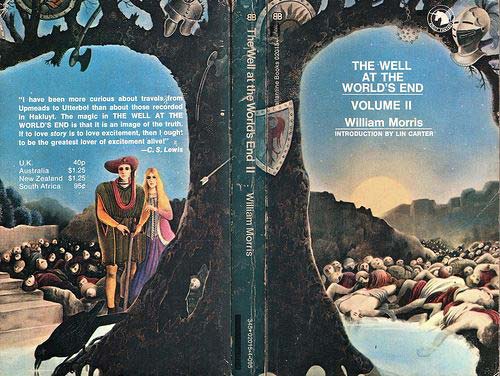

As well as being a leader of the Arts and Crafts Movement, William Morris wrote fantasy fiction, such as The Wood Beyond the World (doesn’t that sound like the Wood Between the Worlds?), The Well at the World’s End and The Water of Wondrous Isles. In The Wood Beyond the World, we find a Lady enchantress with a Dwarf for a servant (sounds familiar?) who keeps a King’s Son in thrall to her (Prince Rillian again?) And the hero, Golden Walter, is referred to as a “son of Adam.”

Lord Dunsanny

Lord Dunsanny’s many short fantasy stories drip with imagination, strangeness and not a little melancholy. I don’t know for sure if they influenced C.S. Lewis, but many of them show how easy it is to go from “the fields we know” – or often from an Edwardian London full of trolleybuses and bowler-hatted businessmen – to somewhere much more mysterious. In other words: “…there could be other worlds – all over the place, just round the corner – like that” (4).

That’s what’s so great about Narnia: the door to it could be anywhere. In a wardrobe, behind the school wall, at the railway station… In one of my favourite Lord Dunsanny stories – “The Wonderful Window” – the hero buys a window which looks out on a castle in a completely different world. It reminds me of the picture in Voyage of the Dawn Treader that takes Lucy and Edmund back to Narnia with Eustace.

This is by no means a full and complete list, so feel free to tell us of any books and stories you think might have influenced the wonderful world of Narnia.

Narnia Photo Credits: Walden Media/ Disney Enterprises

References

(1) CS Lewis, The Horse and His Boy (1954) Chapter 8: “In the House of the Tisroc”

(2) “The Tale of the Ensorceled Prince”, The Thousand and One Nights sacred-texts.com

(3) Quoted on the back cover of Phantastes, Ballantine edition published 1970

(4) CS Lewis, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1950) Chapter 5: “Back on This Side of the Door”

ARE YOU A ROMANCE FAN? FOLLOW THE SILVER PETTICOAT REVIEW:

Our romance-themed entertainment site is on a mission to help you find the best period dramas, romance movies, TV shows, and books. Other topics include Jane Austen, Classic Hollywood, TV Couples, Fairy Tales, Romantic Living, Romanticism, and more. We’re damsels not in distress fighting for the all-new optimistic Romantic Revolution. Join us and subscribe. For more information, see our About, Old-Fashioned Romance 101, Modern Romanticism 101, and Romantic Living 101.

Our romance-themed entertainment site is on a mission to help you find the best period dramas, romance movies, TV shows, and books. Other topics include Jane Austen, Classic Hollywood, TV Couples, Fairy Tales, Romantic Living, Romanticism, and more. We’re damsels not in distress fighting for the all-new optimistic Romantic Revolution. Join us and subscribe. For more information, see our About, Old-Fashioned Romance 101, Modern Romanticism 101, and Romantic Living 101.

Wow. I never even knew. Great post.

Would like to apologise that I spelled Lord Dunsany’s name wrong in this article. Sorry.