I am proud to say that I have a very good eye at an Adultress, —Jane Austen in a letter to her sister Cassandra, 12 May 1801

Jane Austen certainly knew not only how to recognize an adulteress, she also had a remarkable talent for writing about one too; her books are filled with rakes, rattles, and rogues who made sport of toying with ladies’ hearts.

The Elizabethan period witnessed the emergence of the English rogue in fiction, when rogues were considered different from the outlaws of the Medieval Period. Unlike the outlaw, the rogue was not part of any criminal underworld, but instead, symbolized a figure that remained a part of normal society, while simultaneously believing that there was no issue with breaking the law. Perhaps we might acquit ourselves of harboring any affections for her bad boys after all.

Jane Austen even encountered gentlemen rogues in publishing. I was astounded to learn that she self-published three of four books during her lifetime. She received her first contract with a publisher for Susan, much later posthumously published as Northanger Abbey. However, that publisher did nothing with the book but allow dust to collect, and when she applied to have the rights revert to her, she was told that she must return the original ten-pound payment. At that time, she did not undertake the loss. How remarkable that two hundred years after her death, her likeness would appear on the ten-pound note!

“Mr. Murray’s letter is come. He is a rogue, of course, but a civil one. He offers £450 but wants to have the copyright of ‘Mansfield Park’ and ‘Sense and Sensibility’ included. It will end in my publishing for myself, I daresay. He sends more praise, however, than I expected.” —Letter from Jane Austen to her sister, Cassandra, during her negotiations to have Murray publish Emma. —From the Foreward in “Dangerous to Know: Jane Austen’s Rakes & Gentlemen Rogues’ by Claudine di Muzio, JASNA-NY Metro, Regional Coordinator

While she obviously did not condone the shocking behaviors that many of her contemporaries engaged in, she did know that there were at least two sides to each story. Evidenced through her body of work, she created three-dimensional characters, comprised of good and bad, strength and weakness, bravery and cowardice, and all shades in between. Though she does not fully sketch these characters, she understands all too well: How can there be light without the dark?

When you light a candle, you also cast a shadow. —Ursula K. Le Guin

This left me wondering… How did those secondary, even tertiary, characters become the men Jane Austen created? After publishing The Darcy Monologues in May 2017, an anthology of Pride and Prejudice short stories all told from Mr. Darcy’s point-of-view, rumblings began about another anthology. After a collection of stories told from Austen’s most iconic romantic hero, I was curious about her anti-heroes and assembled another gifted group of authors, giving voice to these scandalous men. Perhaps all of Austen’s bad boys are capable of redeeming themselves, and yet, they don’t. Perhaps that was her point: What makes a man a hero or the villain of the story are the choices he makes. Different choices, he becomes a different man—and maybe part of a different story.

RELATED DARCY: THE ULTIMATE BOOK BOYFRIEND (BEFORE BOOK BOYFRIENDS WERE EVEN A THING) – GUEST POST BY CHRISTINA BOYD

In Emma, we know Frank Churchill was a toddler when his mother died. Soon after, his father gave him away to a rich aunt and uncle in hopes of offering him a more promising prospect. As the heir to a fortune, his fine countenance and good-nature added to his manifold of agreeable attributes. Yet all along, he manipulated others to mask his secret engagement to the comely and talented Jane Fairfax, a woman of no fortune. “My idea of him, is that he can adapt his conversation to the taste of everybody, and has the power as well as the wish of being universally agreeable.” —Chapter XVIII.

In writing her anthology contribution, “An Honest Man,” Karen M Cox said, “I actually didn’t decide whether to redeem Frank Churchill [or not] because that wasn’t the biggest issue for me. I wanted to reveal him, in the most excruciatingly honest way I could manage. Frank is the quintessential ‘Teflon Austen Character’—nothing sticks to him. How does he do it?

“I had just recently written a modern Emma adaptation, which helped, as I already had Frank on the brain, so to speak. I’d re-read the novel of course, but to prepare for ‘An Honest Man’, I also studied Shepard’s annotated version of Emma. And interestingly enough, I found on re-reading that Emma’s and Mr. Knightley’s remarks about Frank Churchill gave me considerable insight into his character too. After I’d collected all this information, I sat, pondering: ‘Okay, Karen. You know old Frank pretty well by now. What makes him tick? What would he do to get and keep hidden a beautiful, secret fiancée? How would he spin that situation to make it work out the best for him?’

Because the way Austen wrote him, Frank Churchill is not a villain. He is insidiously selfish, which produces its own brand of villainy. Once I realized that, I knew how it had to go.”

I asked J. Marie Croft to take on the most unlikely rake: John Thorpe from Northanger Abbey. The supercilious braggart, who contrived tales of his own heroics, Thorpe proved to be more than a buffoon but the real villain. Though his ambitions drove him to covet the life of a rake, without the means to afford such extravagance, his character was fixed as a grasping, lying social-climber, whose guile was only surpassed by his sister Isabella’s.

Catherine listened with astonishment; she knew not how to reconcile two such very different accounts of the same thing; for she had not been brought up to understand the propensities of a rattle, nor to know to how many idle assertions and impudent falsehoods the excess of vanity will lead. —Chapter IX.

Having accepted the challenge, Croft said, “The realization I really didn’t want to touch the loutish loudmouth with a ten-foot pole (let alone get inside his stupid head) proved problematic. How could I possibly vindicate a character no one likes?

“Thorpe is downright despicable—more rat than rake, and more rattle than rogue. There’s no way the boorish buffoon would ever attract an Austen heroine … or any human female. But, just as the title of the anthology implies, Thorpe is dangerous to know. He’s a deceiver; and in Northanger Abbey, naive Catherine Morland suffers the consequences of his lies.

“For the record, I don’t suffer liars gladly; and I balked at making one a sympathetic character. So, how did I finally redeem John Thorpe? Well, I didn’t. I failed as miserably as he fails at being the rake he fancies himself in my story. The weasel deserved to be made a laughing stock. Ergo, ‘The Art of Sinking,’ became a farce based, in part, on Shakespeare’s The Merry Wives of Windsor. For a dubious character like Thorpe, a farce—with its ludicrously improbable situations—just seemed fitting.

“Hopefully, though, within that farce, readers will find a crumb of explanation for why John Thorpe is the way he is. Influenced by a blowhard father, and by a mother who approves aversion of truth, and by a selfish, manipulative sister, the rotter couldn’t help but become an irredeemable rat.” Croft adds: “That’s my story, and I’m sticking to it.”

I had tasked Brooke West to take on one of Austen’s most notorious rakes, Henry Crawford in Mansfield Park. Rich, fashionable, and self-satisfied, Crawford was accustomed to having his own way and motivated to find pleasure in all his pursuits. Though not depicted as good looking, his affable and pleasant manners more than countered his plain countenance. He and his sister had been raised by their uncle, Admiral Crawford, who after the death of his wife, invited his mistress to live in their home.

“My dearest Henry, the advantages to you of getting away from the admiral before your manners are hurt by the contagion of his, before you have contracted any of his foolish opinions…” —Chapter XXX.

After an indecent flirtation with the engaged Maria Bertram, he decided to seduce her timid and penniless cousin, only to discover he had indeed fallen in love with the virtuous Fanny Price. On writing “Last Letter to Mansfield,” West said, “Christina’s charge to me: ‘Tell us Henry’s story. Redeem him, if you can. Explain him, if you cannot.’

“Redemption? No. I could not expect readers to accept a Henry Crawford in love and happy. If he had loved before Fanny, he would never have treated her and Maria so abysmally. And perhaps he loved after, but that would have to come much farther in the future than I wanted to peek.

“So, I began with the question asked by every Mansfield Park reader when Henry revisits Maria in London:

‘How could you?!’

“It was clear to me that Henry had never held a true affection for a woman. His cavalier attitude to flirtation and scandal—even to his sister’s well-being and happiness—indicated a young man who had yet to experience the delightful discomfort of putting another person’s desires and interests above one’s own. But neither was he intentionally cruel. I could feel the yearning for approval and affection simmering below the surface of Henry’s flippant encounters.

“Something had happened to take an inexperienced boy and turn him into an unfeeling rake. Pondering this, I knew somehow the admiral was to blame. Like a flash, I was struck with what is, by any measure, a psychologically abusive and unhealthy relationship with his uncle.

“So, the slice of Henry we see is him recognizing the harm his uncle has caused and dancing near to the emotional maturity of realizing the extent of his own blame. The question I could not answer is whether Henry becomes the better man he believes he can now be.”

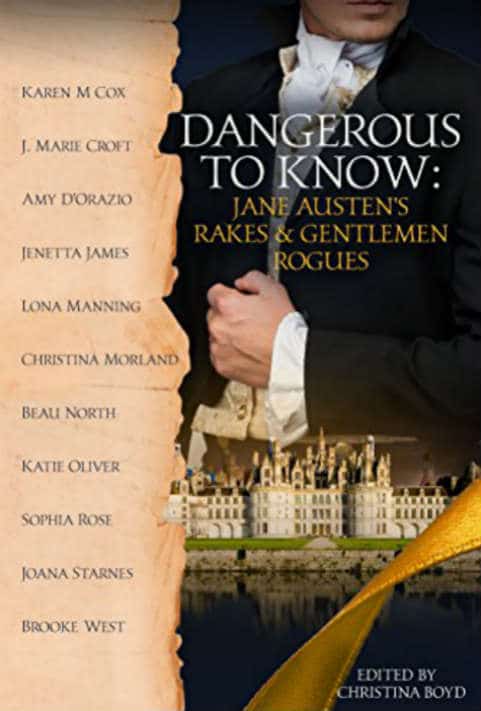

In the spirit of Jane Austen, not all of the eleven rakes and gentlemen rogues could be redeemed in this anthology—if we were to stay true to her characterizations. Like Meredith Esparza at Austenesque Reviews says, “They can’t be like Jane Bennet and make them all good,” so I like to take a pinch from Austen herself, “…from knowing him better, his disposition was better understood.” In Dangerous to Know: Jane Austen’s Rakes & Gentlemen Rogues, tales are shared, secrets are revealed, and hearts are toyed with across Georgian England. I am proud and maybe a little prejudiced to have been a part of this deliciously singular collection of stories aimed to grant Austen’s other men an opportunity to unveil their side of the story as told by a reliable narrator, the rakes and rogues themselves!

ABOUT CHRISTINA BOYD

Christina Boyd wears many hats as she is an editor under her own banner The Quill Ink and editor of The Darcy Monologues, contributor to Austenprose, and a ceramicist and proprietor of Stir Crazy Mama’s Artworks. A life member of the Jane Austen Society of North America, Christina lives in the wilds of the Pacific Northwest with her dear Mr. B, two busy teenagers, and a retriever named BiBi. Visiting Jane Austen’s England was made possible by her own book boyfriend and movie star crush Henry Cavill when she won a trip to meet him on the London Eye in the spring of 2017…True story.

ABOUT DANGEROUS TO KNOW: JANE AUSTEN’S RAKES AND GENTLEMEN ROGUES

“One has all the goodness, and the other all the appearance of it.” –Jane Austen

RELATED BOOK REVIEW: DANGEROUS TO KNOW: JANE AUSTEN’S RAKES & GENTLEMEN ROGUES

Featured image credit at the top: Sense and Sensibility (1995). Photo Credit: Columbia Pictures

ARE YOU A ROMANCE FAN? FOLLOW THE SILVER PETTICOAT REVIEW:

Our romance-themed entertainment site is on a mission to help you find the best period dramas, romance movies, TV shows, and books. Other topics include Jane Austen, Classic Hollywood, TV Couples, Fairy Tales, Romantic Living, Romanticism, and more. We’re damsels not in distress fighting for the all-new optimistic Romantic Revolution. Join us and subscribe. For more information, see our About, Old-Fashioned Romance 101, Modern Romanticism 101, and Romantic Living 101.

Our romance-themed entertainment site is on a mission to help you find the best period dramas, romance movies, TV shows, and books. Other topics include Jane Austen, Classic Hollywood, TV Couples, Fairy Tales, Romantic Living, Romanticism, and more. We’re damsels not in distress fighting for the all-new optimistic Romantic Revolution. Join us and subscribe. For more information, see our About, Old-Fashioned Romance 101, Modern Romanticism 101, and Romantic Living 101.

This was lovely to wake up to just now! Thanks to Silverpetticoatreview for the lovely feature and to Karen M Cox, J. Marie Croft, Brooke West, and Claudine di Muzio for your singular contributions.

You are very welcome! Thanks for the amazing post!

I’m always so curious about what goes into creating the characters of a story so I particularly enjoyed the post. Thanks so much for hosting. 🙂

I’m always curious too! 🙂 You’re welcome!

Loved reading the authors’ comments about the way they approached writing about these rogues.

I loved reading it too. Especially since I love a good rogue!

Thanks, Silver Petticoat Review, for spotlighting Christina today.

Christina, thanks for revealing what Karen and Brooke did with a rake … so to speak.

You’re welcome!