Todd Haynes’ Far from Heaven is possibly the bravest melodrama that I have ever seen. It is a film which accurately reflects the themes, values and visual style of 1950s melodramas. However because of the time it was made and released, 2003, Far From Heaven is much bolder and tackles subjects that those 50s films could only hint at. Todd Haynes wrote and directed Far From Heaven to be about the 1950s as well as a tribute to the melodramas of that time, particularly those of Douglas Sirk.

Though melodramas were popular with audiences at the time of their release, these include Imitation of Life, Magnificent Obsession and All That Heaven Allows, they were often met with condescension by critics, not taken with artistic seriousness and ridiculed for being cheesy. It was not until the 1970s when film critics, film theorists and feminists examined melodramas again and reinterpreted them, appreciating their subversive knack for social criticism and psychological insight using Freudian and post Freudian psychoanalysis.

My personal opinion of melodramas evolved in a similar fashion. For the longest time, I dismissed them as unrealistic soap operas with an excess of everything. It was not until I started taking film classes at university when I developed an appreciation for these films with their subversive nature, use of psychology and their impact on the history of film. Far From Heaven is the film that cemented this newfound appreciation.

Far From Heaven takes place during the autumn of 1957 in Hartford, Connecticut. The Whitakers are the ideal suburban family characterized by family etiquette, social events and an absorption into corporate culture with a husband and wife team known as “Mr. and Mrs. Magnatech.” One night however, the wife and mother Cathy discovers that her husband Frank is homosexual when she walks in on him kissing a man. As her formally perfect life unravels, Cathy finds comfort and friendship with her African-American gardener, Raymond. Gossip spreads throughout the community and several lives are changed forever.

This is a movie that kept me glued to the screen from start to finish, despite the excess of emotion, color and music that melodrama is known for. I was sucked into the 1950s suburban America and I wanted to know what would happen to these characters by the end of the film. This fact may be due to my own personal adoration for social critique and psychology.

Far From Heaven makes me think of a time capsule. It knows exactly what mainstream values were in 1957 and immerses us in them as well as its characters. For example, Frank hates the homosexual part of his identity but he is determined “to lick this problem” and proceeds to do just that with aversion therapy, despite its incredibly unsuccessful reputation. In my opinion, what makes this film work and what makes it powerful is that it is never ironic; there is never a sly hint or a wink to the audience that the filmmakers are more enlightened then the characters on screen. This is a movie that does not know more about the issues that it is tackling then people did in 1957. As there is a lack of irony, the film makes a genuine emotional impact. It is a movie that is fueled by unbridled emotions rather than logic. The effect is rather jolting and by setting the film in a specific time, it is able to shed a brighter light upon the social issues that many people are still dealing with to this day.

One of the film’s strongest themes is oppression. Raymond, Cathy and Frank are all suffering in one way of another and each one is oppressed, albeit at different levels.

I appreciate how the film represents the hypocrisy and euphemism of the 1950s. For instance the dialogue is written in a very stylized way, almost to the point of campiness. Cathy’s son exclaims “shucks” and “jeeze” when she scolds him and a few of Cathy’s friends voice various synonyms for homosexual. When Cathy and Raymond are seen around town together and people begin to talk, Frank, quite hypocritically, screams at Cathy about all he has done to build their family’s reputation while Frank’s homosexuality remains buried and not even brought up.

The themes and messages in this film are obvious and plainly stated, sometimes even by the characters themselves. Far From Heaven is about racism, interracial romance, homophobia, sexism and oppression. I really like how interracial love and homosexual love are treated differently in terms of morality. The civil rights movement predated homosexual liberation by roughly ten years and this is reflected in the film as Raymond and Cathy do not have a plausible future together but there is regret that they do not, while Frank’s homosexuality is treated like a mental illness involving secret meetings with men. The film perfectly illustrates how America in the 1950s would never dare to speak of homosexuality. In order to deepen the social critique of America in the 1950s, Frank’s homosexuality is used to parallel interracial love and racism thus emphasizing the societal stigmatization of the two kinds of love. The movie illustrates how a society’s attitudes can deny individuals from living fulfilling lives. Far From Heaven is therefore a social and political critique.

One of the film’s strongest themes is oppression. Raymond, Cathy and Frank are all suffering in one way of another and each one is oppressed, albeit at different levels. Cathy is oppressed by her role as the perfect wife while trapped in a marriage to a man who does not love her as well as societal racism that will not allow her to be with the man she does love. Frank is oppressed by his internalized homophobia and by a society that will not allow him to live honestly and openly. Raymond is oppressed by the racism that is shown in both the white and black communities.

Though there are several characters in the film, it is the three main ones, Cathy, Raymond, and Frank, whom are given depth, emotional and psychological complexity and feel like real people as opposed to cinema archetypes.

Frank Whitaker is the husband and head of the house. In the public front, he is a successful business man, admired by his peers and known as “Mr. Magnatech.” However, in the private front, he drinks excessively, is filled with misery, does not have much of a relationship with his children or his wife and is hardly ever home. At first, I felt sympathy for Frank considering the emotional, physical and psychological effects of aversion therapy. As the film continued, I found myself having slightly less sympathy for him and noticing selfish tendencies. He takes out his frustrations, both with himself and the therapy, on his wife. He becomes unloving, insensitive, inattentive and cruel to Cathy, both physically and emotionally. He cares more about his reputation then his wife’s feelings or point of view. Some could say Frank is a rather unsympathetic character while other could say he is the opposite and a suffering soul.

Cathy is seen as the perfect wife and mother, almost at a caricature level. She can cook; bake, clean, set tables, plan parties and make cocktails. She is quite popular and admired within her community. She is very loving and understanding. Cathy glows with warmth, curiosity and goodness. Interestingly, there is an air of fragility about her as well as naiveté. She is an optimist and sees the best in everyone and in every situation. Haynes never mocks Cathy’s happiness, even as it begins to unravel. With the discovery of Frank’s homosexuality also comes with it the innate realization that her life with Frank has been nothing more than an illusion of happiness. Cathy also begins to see the contradictions and xenophobia that plague her inner circle of friends. Through the course of the film, Cathy slowly breaks out of her safe cocoon she knew as her old world, to see the world for what it really is: full of hypocrisy, racism and sexism.

Raymond Deagan is the cultured and college educated son of the Whitakers African American gardener. He has a business degree but he takes over his deceased father’s work, running a garden business in town. He is a widower and dotes on his 11-year-old daughter. He is a devoted father and wants to do what is best for his young daughter. He is very kind, reserved, gentle, charming and understanding. He is also quite observant, often noticing things about the people around him that seem out of the ordinary without needing many words of explanation. He is quite intelligent and enjoys philosophy. He also has an appreciation for art as shown in a scene when he and Cathy are in an art museum discussing modern art. He is also very open-minded and sees things beyond the surface level. This is evident in all who he interacts with, especially Cathy. Another interesting point is that his masculinity is used in sharp contrast with Frank.

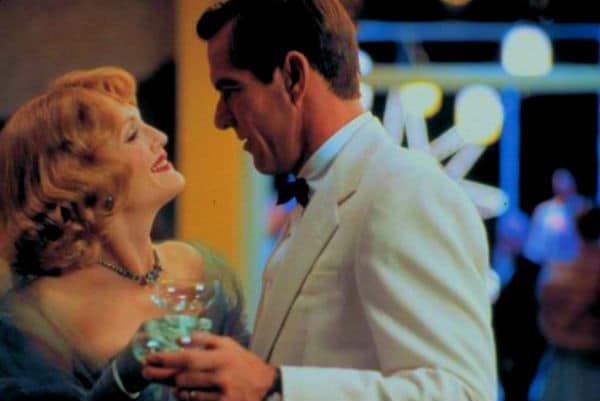

Personally, I thought the relationship between Cathy and Raymond was well developed and believable. I love interracial romances and watching how completely different cultures can come together and learn what they can about each other. I think it is a really beautiful thing. Their relationship is chaste, tender and fragile. Both Cathy and Raymond are filled with mutual, sweet but poignant longing that is expressed through subtlety due to the times they are in. They have so many moments during the film, a lingering look, a touch, a kind word; those smiles… and pretty soon I found myself really enjoying their scenes together. This is not to say however, that the film portrays a plausible way for Cathy and Raymond to be together because they do not. There is a bittersweet regret that permeates throughout the movie that they do not, a regret that is made even more tender because they acknowledge that their society will not accept them as a couple. Furthermore, by placing them in such a repressive setting, their story becomes even more moving to the viewers.

Melodramas are well-known for their excess of everything from the emotions and events to the colors and music. One of the greatest strengths of Far From Heaven is how through a combination of its visual style and music, it feels and looks like a movie from the 1950s. The costumes by the wonderful costume designer Sandy Powell look as if they were taken out of a fashion magazine from the 1950s in the best possible way, with the circular skirted dresses and flannel suits of dark colors. The film is filled with rich, saturated colors and an exaggeration of moonlight, sunlight and stark contrast between shadows and light. Edward Lachman is the cinematographer and he successfully reproduces the lush studio style of the 1950s. For example, the film opens with a downward crane shot of blood-red maple leaves which echoes the opening in Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows. Elmer Bernstein is the composer for the film and his music scores help tell the story and portray what a character is feeling, often without very much dialogue.

There are many scenes that can be used as an example and one very good one is a scene with Cathy and Frank Whitaker that takes place shortly before the halfway point of the film. Cathy has already found out about her husband’s homosexuality and he has been in therapy for it, believing wholeheartedly that he can “beat it.” It is late at night, the Whitakers had thrown a party earlier in the evening with Frank becoming more inebriated then any of their friends had seen. As Cathy voices her feelings about the events of the party, Frank holds her and kisses her in an almost desperate fashion. Eventually however, he pulls away from Cathy, becoming angry and frustrated with himself that such actions do not have the same physical effect on him that they do with a man. Cathy tries to comfort him but Frank’s emotions get the best of him and he hits Cathy. Cathy backs away and holds her head in pain. Frank is overwhelmed with guilt, remorse, and disgust with himself for what he did and goes to get ice for Cathy.

Melodramas are well-known for their excess of everything from the emotions and events to the colors and music.

The scene has an excess of saturated, rich colors. The characters are illuminated by moonlight, despite the fact that in reality moonlight would not have the intensity of color and stark contrast with shadows that this scene has. This contrast is a way to create tension and conflict within the characters. By lying on the couch, the tension builds between Cathy and Frank, surrounded by more shadows which hint at the eventual emotional eruption from Frank. The use of shadows is also suggestive of dark undertones such as the self-hatred Frank feels and the feelings of helplessness of Cathy in how there does not seem to be anything she can do to help her husband.

There is also an excess of music in this scene as well as throughout the entire film to help define a character’s psychological and emotional states. The instruments used in this particular scene are violins which are often used to convey strong emotions such as laughing and crying. The violins begin rather abruptly when Frank first kisses Cathy. As they continue to kiss, Frank’s movements take on a tone of desperation the music continues to build but it is in a minor key thus hinting to the audience that this is not a joyful moment between the couple. When Frank finally pulls away from Cathy and deprecates himself, the music swells and the violins are utilized to imitate wailing, perfectly illustrating Frank’s feelings of despair. The music for the remainder of the scene, aside from when Frank hits Cathy, is subdued and keeps the melancholy tone of the scene intact without the characters having to speak very much at all.

Far From Heaven is a film that sheds a light on a genre and a time period that is often subjected to parody and gives it a sense of humanity. I would recommend this film to not only people who enjoy melodramas and the work of Todd Haynes, but also to those who like period pieces and stories with deep and important themes. Far From Heaven explores these themes because they are universal; they are things that we are still dealing with to this day. It accomplishes this through a well-written screenplay, wonderful acting, characters we can connect with, lovely cinematography and evocative music. It may not be from a film genre that is the most popular, however, I think it is a film that earned its various critic choice awards.

Content Note: This film is rated PG-13 and has brief strong language and some sexual content – though not explicit.