Welcome to Revisiting Disney! Sorry about last week and thanks for bearing with me, but now we’re back with a vengeance to take a look at one of my favorite Disney movies as a kid, Sleeping Beauty! As always, I’ve labeled each category, so if you want to skip to the parts that interest you most, feel free. And, of course, if you have any thoughts, burning or otherwise, please share in the comments!

Like Cinderella, I grew up loving Sleeping Beauty. The music, the animation, the characters, the story, the adventure…it was, to me, one of the best movies (eclipsed only by Beauty and the Beast). We had a recorded VHS copy, and the beginning had been partially taped over by the end of Ghostbusters (it occurs to me that I should thank my parents for realizing that that was the Sleeping Beauty tape and not taping over the whole thing).

RELATED: Revisiting Disney: Cinderella

Due to the way I watched the film as a young kid, I was always very interested in what happened before Merryweather gives Aurora her gift (as that was where Ghostbusters ended and the Disney magic began). I’d read the book, both by myself and by asking my parents to read it to me over and over again, so I did know what happened. I just hadn’t seen it very often. And even today, I find the beginning with the parade to be a bit out of place though I love when the Three Good Fairies appear. Maybe I’m just looking for the State Puff Marshmallow Man.

As a college student, there were times when I found myself frustrated with the characters, and a friend and I used to wish that they would consider their choices a little closer. Things would be better if they had just done things our way.

Despite that, unlike with Cinderella, I never had a moment where I hated this film. The artistry and the music were enough to make me like Sleeping Beauty pretty consistently. The characters were memorable, there were some hilarious lines, the score is one of my favorite pieces of music to this day and the villain is absolutely fantastic. We’ll get to her, I promise.

That’s a bit of my background and attachment to this particular film. You may have noticed that some of these films were ones that I remember adoring as a kid (so the Dumbo phase doesn’t count because I don’t remember it), others I liked and some I had never heard of before (also, some of these came out when I was an adult, so there’s that). One final note, this film is highly visual; it’s felt more like an art piece than some of the others have.

BACKGROUND

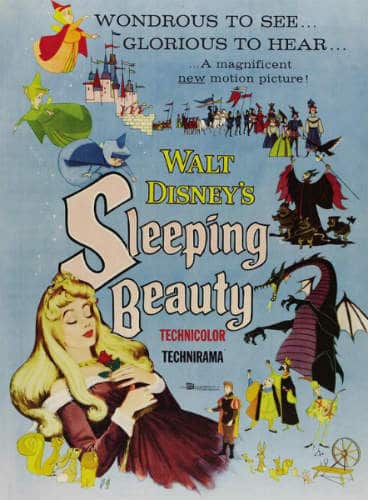

Sleeping Beauty was released on January 29th, 1959 and featured taglines such as “Wondrous to see…Glorious to hear…A magnificent new motion picture!” And really, even removing the all-powerful nostalgia goggles, it is.

Sleeping Beauty joins the list of Disney films in production for a long time, but in this case, it wasn’t just story work that spanned almost a full decade. They started work in 1951, and the voices were recorded in ’52. The animation took five years (spanning from ’53 to ’58) and the score was recorded in ’57. Basically, this was a huge undertaking.

This was also the only Disney film (other than The Black Cauldron) to be shot in Technirama and it was the last Disney film that used cells that were inked by hand. From this point onward, the studio would use Xerox technology instead. Although some scenes in Sleeping Beauty used that process, mainly it was hand-inked.

Despite the fact that, due to the Disney Studio’s habit of re-releasing their animated films in theaters, Sleeping Beauty is actually the second highest grossing film to come out in 1959 (right behind Ben-Hur), it was not received favorably at the time.

Adrian Bailey says that a live-action feature by Disney released in the same year, The Shaggy Dog, actually made almost twice as much money as Sleeping Beauty, and probably cost a whole lot less. He goes on to say that the film was supposed to be “the Studio’s magnum opus, the last word in advanced techniques and splendor of presentation” (Bailey 1982:193).

Bailey acknowledges the talent assembled, the cutting edge technology used and the beautiful score, but says that the film’s style seems “sterile and cold,” and that it failed to capture audiences (Bailey 1982:193). Sleeping Beauty cost 6 million to make, but at the time only made 5.3 million. It would later make that up, but it was still a blow.

He wonders if the failure of Sleeping Beauty was due to the end of the fairy tale in animated films, making way for films that had more in common with Lady and the Tramp and 101 Dalmatians, or if it had more to do with Walt Disney’s busy schedule, Disneyland was being constructed at the time, and he was less hands-on than he had been in earlier films.

Other animation historians have similar things to say. Finch talks about the film as “a wide-screen feature that began with high hopes and ended in disaster,” and one that was “greeted with a pervasive lack of enthusiasm,” and Bob Thomas has similar complaints (Finch 1975:120-1). All three historians think that a driving force was that the time for animated fairy tales was over and that the Studio would take a cue from the success of Lady and the Tramp in their future films.

RELATED: Revisiting Disney: Lady and the Tramp

MUSIC

The music for Sleeping Beauty is based on the “Sleeping Beauty” ballet composed by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and recorded by the Berlin Symphony Orchestra. The Studio arranged the ballet to suit their needs. For example, the opening of the film is actually part of the ballet’s second movement, and the music used for the scene where Aurora is under Maleficent’s spell is actually a comic number in the ballet. Other themes and movements were stretched out to fit the score’s needs. It works beautifully and was nominated for an Oscar in 1960 in the category of Best Music, Scoring of a Musical Picture.

George Bruns did the scoring for Sleeping Beauty, as well as working on 101 Dalmatians, The Jungle Book, Robin Hood and The Aristocats. Bruns was born in Oregon in 1914 in a logging town and was proficient on the piano, tuba and trombone. Although he attended college, he left to pursue a career as a musician. He died in Portland in 1983.

Bruns had started work on the score in LA using a 4-track stereo, but then he heard about a studio in Berlin with a 6-track stereo. so went there to record instead. Some think that was a definite contributor to the Oscar nomination the score received in 1960.

Sleeping Beauty was also nominated for a Grammy in 1959 for Best Soundtrack Album, Original Cast-Motion Picture or Television. If you think about it, that is really a broad category, isn’t it? Winston Hibler and Ted Sears wrote the lyrics for “I Wonder,” Sammy Fain and Jack Lawrence wrote the music and lyrics for “Once Upon a Dream,” Erdman Penner wrote the rest of the lyrics, and Mary Costa and Bill Shirley sang their own parts (wonderfully, I would say). The choral arrangements were done by John Rarig, and the addition of the choir made the whole story seem that much more epic.

Sleeping Beauty was unique at the time in that it didn’t just have the songs sung by the characters; it also had the orchestral score, which caught on in later soundtracks. The soundtrack is one of those things that people remember about this movie. Although the music is fantastic and scored beautifully, it doesn’t overwhelm the dialogue. It supports it in a wonderfully understated way, just like I think a good score should.

ANIMATION

The animation on this film has always fascinated me, mainly because of the way the character and the backgrounds play off of each other. I always got the sense that it must have been challenging to keep the background from overwhelming the characters (turns out I was right) and that the style was an interesting mix of modern and older art.

In the Disney Studio’s documentary on the making of Sleeping Beauty, modern Disney Lead Animator Andreas Deja says that Sleeping Beauty “takes the ideas and the colors and the motifs from the Middle Ages, but then it reinterprets those with a ‘50s point of view, it being very graphic and there’s a certain sort of a…sputnik style, graphic style that happened in the ‘50s.” Looking at the film and the way the story fit together, he says that very well.

Animation clashes occurred because Walt had assigned Eyvind Earle to work on the backgrounds, and given him complete artistic control over the piece. Earle was in charge of color styling, which meant that all colors went through him to give the piece an overall uniform aesthetic look and feel. He drew with what was called the modernist approach to reinterpreting pre-Renaissance art. Animation historians frame it saying that “Earle was captain of the team.”

Eyvind Earle was born in Manhattan in April of 1916 and passed away in July of 2000 in California. He had worked on Lady and the Tramp, which is, according to the Disney Studio’s short documentary about his life, is when Earle became first noticed by Disney. He had a very rough childhood, including being essentially kidnapped by his abusive father and taken on a trip around Europe where he was forced to complete a painting a day. By the time he was 13; Eyvind was an established artist (according to his IMDB page) and sold his first watercolor to the Met in New York at age 23.

The artistic style of Sleeping Beauty was based on the unicorn tapestries at the Cloisters in New York. John Hench had brought reproductions to Walt, who loved the idea of incorporating that style into Sleeping Beauty. Earle was further inspired by pre-Renaissance art, Persian art, and Japanese prints, using what Thomas called “primitive technique” (Thomas 1997: 105).

One of my favorite quotes regarding the animation for Sleeping Beauty comes from historian Bob Thomas, saying that “the backgrounds were stunning to the eye but hellish for the animators” (Thomas 1997:105). This made it difficult for the animators, as they had to create characters that could hold audience attention and stand out against the background without clashing with it.

As for the animators, most of the Nine Old Men were present (Ward Kimball being the only one not involved); the directing animators were Milt Kahl, Frank Thomas, Marc Davis, Ollie Johnston and John Lounsbery, while Eric Larson, Wolfgang Reitherman and Les Clark were sequence directors. Don Bluth was also involved in production as an assistant animator.

Animator Frank Thomas recalled to Thomas that he found the “Gothic style impossible to work with” because of the constraints of the style (Thomas 1997:105). He also mentioned in various special features that he had worked very hard to give Merryweather an impression of weightlessness in the cleaning scene. However, he was instructed to give her a black bodice, which he felt weighed her down.

The animators clashed with Earle on several points relating to coloring and styling of their characters. Earle won most of the big battles, but in some cases, the animators had some victories. Ollie Johnston and Frank Thomas were able to convince the leads that the three good fairies should have distinct personalities, which I think worked for the better.

Other notable things to mention are that Marc Davis animated both Princess Aurora and Maleficent, John Lounsbery animated the scene with the two kings and the jester, and Milt Kahl animated both Prince Phillip and Sampson the horse. The live-action footage that was shot for the animators is rare, but if you can track it down, it’s well worth the watch. Clips are on most DVD copies, as well as on the second VHS release (the Masterpiece Edition).

Finch reminds me that Sleeping Beauty was shot in a new style, Technirama 70. As near as I can understand, this is because the two 35 mm negatives are combined to create one 70 mm negative and then shot through what Finch calls an “anamorphic lens” (Finch 1982: 193). This allows for a wider view but also means that all the animation has to be that much more detailed, which worked out well, considered Earle’s backgrounds paid incredible attention to detail.

Bob Thomas’ words to describe how Sleeping Beauty was received are impressive. He acknowledges that the design was “impressive” but reminds us that “critics called Sleeping Beauty pretentious and audiences were unmoved” (Thomas 1997: 105).

THE PLOT

Our story opens up with a beautifully illustrated book that opens to tell us the story of Sleeping Beauty, and then transitions into a parade of people coming to pay homage to the baby princess Aurora. These people include neighboring King Hubert and his son Prince Phillip, who is betrothed to the baby Princess and the three good fairies, Flora, Fauna, and Merryweather.

The fairies, of course, have gifts for the baby. Flora gives her beauty, Fauna gives her song, and Merryweather is interrupted by the arrival of Maleficent, the evil fairy. Maleficent is offended to have not been invited and, to prove that she is not offended, curses the baby. The curse is that “before the sun sets on her sixteenth birthday, she will prick her finger on the spindle of a spinning wheel, and die.” I think that’s overkill, don’t you?

Luckily, Merryweather hasn’t given her gift yet, so she is able to counter the curse. Maleficent is too powerful for her to overrule it, but she makes it so Aurora is just sleeping until her true love kisses her.

As an aside, as a kid I was always really curious as to what Merryweather’s gift would have been. I always figured it was wisdom, diplomacy or dancing, and I never thought it was fair that she had to change her gift. She had probably carefully picked it out and everything! Though to be fair, she’s the one that got all sassy and made Maleficent mad, so serves her right? Despite that, and maybe because of it, Merryweather was always my favorite of the three good fairies. Not only did she have the best lines, she got to dance with the mop, which I always thought was quite cool.

The three fairies hatch a plot to take Aurora away and raise her in the forest, where she will be safe until her sixteenth birthday. They call her Briar Rose and vow to not use their magic, to prevent Maleficent from finding them. To be honest, some of the fairies’ attempts to do things without magic are some of the best and funniest stuff in the film.

We cut to Maleficent’s lair and learn that she has the worst henchmen every. They have been unable to find Aurora because they’re been looking for a baby for the past 16 years. Maleficent is pretty mad at them all and sends out her raven to find the princess.

At this point, we go back to Aurora and the fairies on Aurora’s 16th birthday. They want to give her a birthday party, with a cake and a new dress. As they divide up the tasks, I can’t help but wonder what Merryweather doesn’t do around this house. She comes up with the idea that gets Aurora out of the house and is also the only one who understands the concept of sewing and knows what tsp stands for.

Meanwhile, Aurora sings her way through the forest with her woodland friends. A stranger who happens to be Prince Phillip riding through the woods hears and is curious about who is singing. This segment of the film gives us both Aurora’s “I Wonder” and the classic and much loved “Once Upon a Dream.”

Aurora is feeling a bit blue and her animal friends try to help her feel better by stealing Prince Phillip’s boat, cloak, and hat and coming back to dance with her. He follows them to find Aurora and cuts into the dance. When she mentions that they don’t know each other, he responds that they met once upon a dream, sings her song and waltzes through the forest with her.

It’s such a sweet and romantic scene (mostly because it’s a fairy tale and not real life. It would be creepy in real life. Think about it). Quick animation note, this was one of the hardest and most expensive scenes to animate; Walt was very particular about how he wanted it to look. Of course, Phillip and Aurora don’t know each other’s names, let alone that they’re betrothed, and technically, we haven’t been told he’s Prince Phillip yet.

Aurora has to run home but tells Phillip to come to her house to meet her guardians at her birthday party that night. Then we cut back to the fairies, who are truly making a mess of things. Merryweather makes an executive decision and gets the wand, which fixes things but, after a magic color-battle between herself and Flora, Maleficent’s raven finds them and learns both that Aurora is going to go home that night and that her true love will be in the cottage that evening.

Aurora is heartbroken to learn that she’s a princess and is going to marry some guy she’s never met before (fair enough). Interesting note, the animators and color team were unable to decide between pink and blue for Aurora’s dress, making the conflict between Merryweather and Flora throughout the film much funnier.

Two things have always bugged me about the scene where they take her home and the fight over the dress’ color. First, why didn’t they compromise and make the dress purple, or green (like Flora’s clothes?) Second, why didn’t they all wait to bring her back to the palace until the day after her 16th birthday, or celebrate her birthday the day after? Then they know she’s safe. That, to me, shows poor planning. I mean, come on!

There’s an amazing scene where kings’ Hubert and Stefan fight about their kids not liking each other (ironic, because they’ve already fallen in love at this point). It’s a hilarious scene because of that irony, and it’s very cleverly animated. After this scene, Phillip arrives to tell his father he’s not marrying Aurora, he’s in love with a peasant girl and going to her house for dinner. This is awkward because now Hubert has to tell his best friend the news.

Back to Aurora, she’s heartbroken, and the good fairies, in another moment of dumbness, decide to leave her alone. Maleficent takes advantage and hypnotizes the poor bewildered princess into following her and touching the spindle. Why? Why would you leave the emotionally vulnerable princess alone when the evil fairy is waiting for a chance to pounce and has only 10 minutes or so? Why not just wait the 10 minutes? I just…moving on.

Because they don’t want everyone to be broken-hearted, the good fairies put everyone in the kingdom to sleep until Aurora wakes up. While this is occurring, Flora discovers that Phillip is the man Aurora met in the woods and they rush to get him, only to find that they’re too late.

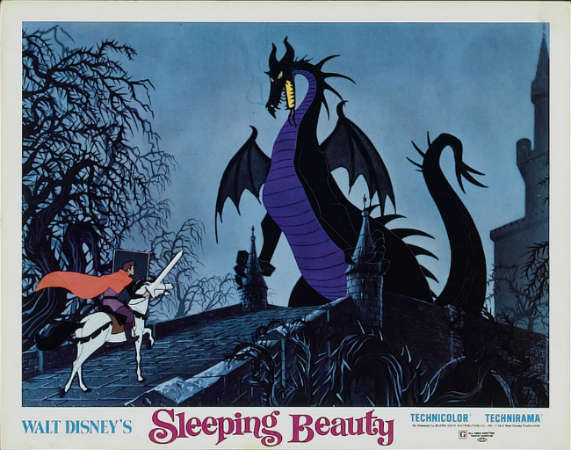

Maleficent and her inept henchmen got there first, and through numbers alone took Phillip and Samson back to their lair. The good fairies launch a rescue mission, and Maleficent gets in some good gloating. After freeing him from his chains, the good fairies give Phillip the Shield of Virtue and the Sword of Truth to help him escape. What follows is what I would call one of the most climatic scenes in a Disney movie, ever.

It’s basically ten minutes of him escaping and fighting the bad guys. It shows him still charging forward, even though Maleficent is throwing everything she has at him. When he busts through the thorns, she decides to fight him herself and turns into a fire-breathing dragon. The next five to ten minutes are just as exciting, watching the battle rage as the thorns begin to burn. It’s so exciting, I lose track of time every time.

Of course, it’s a Disney movie, so good triumphs over evil, Phillip finds Aurora, kisses her, she wakes up, and everyone else wakes up. Phillip and Aurora come down the stairs, hug their parents (well, she does. He’s a prince. They don’t hug people), and the film ends with a waltz, a nice call-back to the meet-cute. And, of course, they all live happily ever after (though no one can decide what color Aurora’s dress should be. It’s still changing color as the book closes).

There are two major characters that I want to talk about, at least a little bit, starting with Maleficent and moving on to Prince Phillip.

Maleficent is really a fascinating character. She curses a baby out of spite, relentlessly fulfills her curse, and kidnaps the only person who could break it. She’s also mean to her henchmen and insults the other magical people in her community. Her character design is amazing and she has a phenomenal voice actress, Eleanor Audley. Not only that, she can make thorns grow up around an entire castle and turn into a dragon.

It’s also interesting to me that Maleficent set up what could almost be seen as an obstacle course around her curse. She had to use a specific weapon and only had a certain window of time. It’s like she thought that everyone else in the kingdom were idiots and wanted to make it interesting and challenge herself. As far as villains go, she’s terrifying, cunning and kind of cool all at the same time.

RELATED: Behind the Fairy Tale-Maleficent

Prince Phillip is also a pretty cool character, as far as Disney princes go. He can sing, dance, has a great horse, stands up for love, is only taken prisoner because he was outnumbered 20 to one (they tied his hands first thing, and he manages to get one free and cause a lot of trouble), he hacks through a forest of thorns, and fights a dragon.

I’ve heard him called a cardboard character, and while I can see it, I also think that while he doesn’t have as much depth as Disney Princes from the ‘90s and early 2000s, he has much more than the previous Disney princes. The fact that Aurora is out of commission with the whole curse thing puts him in a place of being a more active part of the story, and I think that’s pretty neat.

SOURCE MATERIAL

Officially, Sleeping Beauty is based on the Charles Perrault fairy tale of the same name. However, it can be argued that the story actually has more in common with the Grimm Brother’s version of the story.

There are several versions of Sleeping Beauty, and most of them have the waking up of the titular princess as the halfway point of the story. In one version, “Sun, Moon, and Talia” by Giambattista Bastile that was published in 1636, Talia is awakened when one of the twins that she gives birth to nine months after the king’s visit sucks the piece of flax that is under her nail out. The king’s wife is insanely jealous and tries to kill the three. She dies instead, however, and the others live happily ever after.

The Perrault version, “Sleeping Beauty in the Wood,” was published in 1697. The moment that the prince kisses the sleeping beauty is actually the middle of the story. They get married, have two kids, and things seem to be going well. When the prince has to go to battle, he trusts his mother to look after his family.

Sadly, the queen is a cannibal who tries to kill her son’s family. Luckily, the princess and her children are saved by a kind servant and the prince catches his mother trying to kill his family. This causes her to commit suicide. You can see why Disney left that part of the story out.

The Grimm Brothers used the name Briar Rose for their princess and, although there are several notable differences in the two, this is the closest to the Disney version. In this version, the king and queen just ran out of plates for the wise women, so one was left out. She showed up, feeling insulted and cursed the girl.

The rest of the opening is basically the same from story to story. In most versions, the curse either lasts 100 years or that was the final fairy’s way to cancel out the death part of the curse. In those stories, she also stayed at the castle and was tricked by the fairy who was in disguise as an old woman spinning.

In other stories, many princes had tried to go through, but the hedge of thorns that had grown up around the castle killed every man until the 100 years had passed. This was hinted at in Maleficent’s plot, as she was going to release Phillip in 100 years to break the spell, but Aurora and her parents’ court spend comparatively little time asleep. I think the Disney version is more kid-friendly, which is probably why the Studio made the changes that they did.

The 1950’s

According to Maria Tater, who wrote the annotated fairy-tale collection, the gifts that the princess received were supposed to turn her into an ideal woman. The Grimm Brothers version had her receiving virtue, beauty, wealth, etc, while Disney gave her beauty and song. If that theory can be carried to the Disney version, this shows the importance in the ’50s for a woman to be beautiful and talented in some way.

I already mentioned in the animation section the impact of the ’50s style of art on this film (it’s toward the top, so check that out). I also talk briefly about Phillip’s armor in the lessons section, so look for that, too.

The other thing that I find very interesting about this film is that Aurora owes her style to the Gibson Girl. What is a Gibson Girl? I’m glad you asked. The Gibson Girl was designed by Charles Dana Gibson and was very popular around the turn of the century. She was the New Woman, sophisticated and stylish, rising out of the idea that “physical beauty was a measure of fitness, character, and Americanness” (Kitch 2001:40).

Carolyn Kitch points out that the Gibson Girl was really only prevalent during the first decade of the 1900s, but she did give rise to the idea of the Ideal American Girl. Similarly, most Disney leading ladies owe their look to what was considered the Ideal at the time of her movie, which is where the Aurora/Gibson Girl connection kicks in.

The Gibson Girl design was used and adapted in American advertising. She had the added advantage of allowing women of all walks of life to strive for the same look in fashion and hair, so marketing firms appreciated her. Gibson’s Girl was replaced by Fisher’s Girl, very similar idea but with features that were slightly more rounded than the Gibson Girl’s features. She would in turn give rise to a new standard of feminine beauty, and so the cycle goes.

Aurora, however, is to me more stylistically similar to the Gibson Girl than the Fisher Girl, perhaps in a call back to classic standards of beauty. All decades are nostalgic for previous ones, and the ’50s could easily have been nostalgic for the turn of the century.

When it comes to feminine standards of the ’50s, Kitch calls it “seductively sweet,” referring to Doris Day, and “golddiggingly ditzy,” in reference to Marilyn Monroe (Kitch 2001: 185). IMDB tells me that Princess Aurora’s body shape was inspired by the actress Audrey Hepburn, who was looking in a similar way as Doris Day; wholesome, innocence and classy.

The impact of Audrey Hepburn on the standards of feminine beauty of this era can be seen in the design of Aurora. Even Aurora’s character traits emphasize her innocence and wholesome upbringing, and can be said to be influenced heavily by the time period she was created in.

I feel like Aurora gets a bad rap because she’s not an active character, to which I want to point out that it’s called Sleeping Beauty. For the story to work, the beauty has to be asleep. This is not, as I’ve heard, drawing from feminist inequality of the ’50s and saying that women are prettier when they’re silent; it’s staying true to the source material. The most powerful characters in the story are Maleficent and the fairies and they are all women.

Yes, Maleficent is killed by a man, but that’s a fairy tale. The hero kills the bad guy, but he needs help to do it. He may do the fighting, but the fairies give him the tools and bust him out of prison. The feminist movement was brewing in the ’50s, so this could be a result of that, or it could be as simple as the fact that the fairies in the source material are women, and Eleanor Audley does an amazing villain voice.

LESSONS LEARNED

The first major lesson learned from this story is that when you have magical beings in your kingdom, don’t invite all but the most powerful to the christening. If Maleficent had been invited, she might have given a curse-gift, but she might have had something awesome, to show up the three fairies that she hated and considered weak.

If you don’t invite a powerful and vengeful magical person to your party, don’t insult them when they show up irritated. I think this can be summed up in a real-world application by the simple phrase, “don’t be a jerk.” If you’re polite, it usually works better for all involved.

The second lesson I learned was to use your head. It’s important to think things through. If a vengeful fairy is after your ward and wants to kill her in a very specific way for a curse that expires at sunset on her 16th birthday, maybe keep her hidden until after sunset? Just, try to think things through and do your best. Similarly, if you have a shield, use it!

Another lesson is that true love will triumph over all adversaries, which is reassuring. However, it’s not just true love that can conquer evil. The Shield of Virtue and the Sword of Truth are, in some traditions, part of the Armor of God, worn to defend the wearer and those he or she is defending from the forces of evil that are seeking to tear them down. I’m oversimplifying here, but that’s the gist. The use of these two pieces of armor, therefore, has a root in Scripture.

These weapons can also serve as a tie to the everyday life that was part of the ’50s (and carry on into the present as well). Billed as the simpler days, truth and virtue were values held in high regard in the 1950’s. The takeaway here is simple. If you live virtuously and defend yourself with the truth, you can defend yourself against any evil that comes at you; gossip, slander or just plain spitefulness. The weapons of righteousness, as Flora says, will triumph over evil. Not just can, will. So virtue and truth are two of the greatest weapons in our arsenal.

DOES IT HOLD UP?

Although it was not critically acclaimed in its day, and some have called it cold and sterile, I still love this movie. Honestly, I think it looks great. The backgrounds are busy, but there is something new to see every time. The characters are fun, the villain is fantastic and the last 15 minutes are some of the most exciting to ever be animated. The music is classic, the voice actors are great and the animators and artists were truly some of the greats.

I never felt like it was a clinical story, either when I was a jaded college student or as an idealistic small person. But then again, I was dancing and singing in the woods and waiting for my woodland friends to come dance with me as a kid, and in college I was way too interested in the style of animation to care about most anything else.

Today, I can see the flaws in the film, but to me, the struggles that the animators went through to create the film, the amount of time spent working on it, the sheer amount of talent involved and the legions of people that now love it, all work together to make it that much better.

Sleeping Beauty is a unique and one of a kind film, and other film historians say that regardless of the cost analysis, it’s a gorgeous film, just for the artistry. For me, it’s the kind of story that I walked with, once upon a dream.

OTHER SOURCES:

http://www.history.com/topics/1950s

thewaltdisneycompany.com/about-disney/disney-history

http://studioservices.go.com/disneystudios/history.html

Bailey, Adrian. Walt Disney’s World of Fantasy. Everest House Publishers. New York, New York. 1982.

Finch, Christopher. The Art of Walt Disney: From Mickey Mouse to the Magic Kingdom. Harry N. Abrams, Inc. New York, New York. 1975.

Kitch, Carolyn. The Girl on the Magazine Cover: The Origins of Visual Stereotypes in American Mass Media. University of North Caroline Press. Chapel Hill and London. 2001.

Sale, Roger. Fairy Tales and After: From Snow White to E.B. White. Harvard University Press. Cambridge, MA, 1978.

Tatar, Maria. The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales. W.W. Norton and Company. New York and London, 2002.

Thomas, Bob. Disney’s Art of Animation From Mickey Mouse to Hercules. Hyperion. New York, New York. 1992.

Wright, Gordon. The Ordeal of Total War: 1939-1945. Harper Torchbooks, Harper & Row. New York, Hagerstown, San Francisco, and London, 1968.

I’m amazed, I have to admit. Seldom do I encounter a blog that’s

both equally educative and engaging, and without a doubt,

you’ve hit the nail on the head. The issue is something

that too few men and women are speaking intelligently about.

I am very happy I found this in my search for something regarding this.